Stereotyped Killer Whales or Friendly Orcas?

by Noah Patton

The Killer Whale or Orca is a toothed whale belonging to the Delphinidae (dolphin) family. It is the largest member of the family with males growing up to 9 metres in length and is an apex predator – meaning that no animal, except humans, prey on them. Their genus name Orcinus is translated from Latin to “of the Kingdom of the Dead”, with Orca also meaning whale. This is likely where the commonly used term Killer Whale originates from, but the term orca is growing in use as it avoids the negative connotation of being a “killer”.

The stereotype of orca being “killers” originated from early times. The ancient roman author Pliny the Elder was the first to give a description of an orca, describing it as “an enormous mass of flesh armed with teeth… with its teeth tears its (other whales) young, or else attacks the females which have just brought forth, and, indeed, while they are still pregnant.”[1] Despite their brutal efficiency in hunting other mammals, they have been historically harmless to humans in the wild. There are very few recorded wild orca attacks on humans. Of the recorded attacks, there have been no fatalities and few injuries.

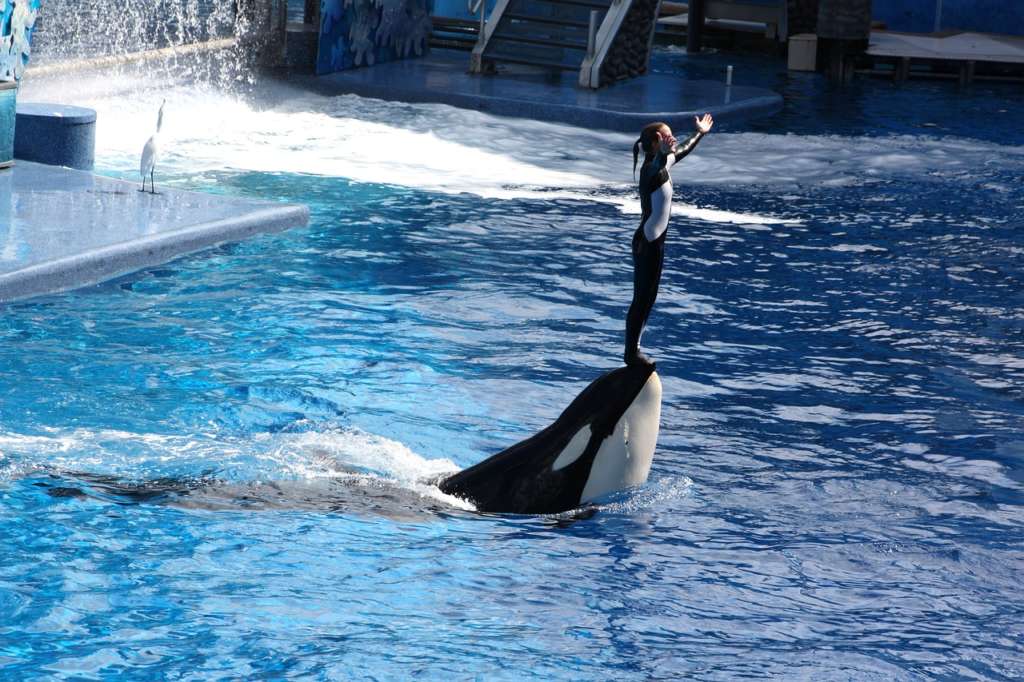

The same cannot be said for captive Orcas. Distressingly, there have been over 37 recorded attacks on humans by captive orcas, six of which ended in the deaths of people.[2] The 2013 documentary Blackfish follows the Orca, Tilikum, responsible for three of these deaths. The documentary argued that the captivity and poor treatment of orca’s is the catalyst for the aggressive behaviour seen in the species. SeaWorld responded to the documentary calling it “propaganda”.[3] Despite this statement, their blog post critical of the documentary has been deleted and since 2016 all orca shows have been shut down.

Living up to 90 years of age, Orca have been identified by researchers to have three distinct types in the northern hemisphere, but these are not yet considered distinct enough to split into separate subspecies or species.

Residents are the most common, they roam in the coasts of the northeast Pacific but can be found from Japan to Russia as well. Their main diet is fish and squid. Residents travel in family groups called pods. Individual pods will migrate between the same areas consistently.

Transients or “Bigg’s” Orcas roam further north along the Arctic Circle, Alaska and California. They travel in very small groups of two to six orcas and have significantly less family bonds than the other types. Transients primarily hunt marine mammals.

Offshore orca travel far from the coasts of any area, choosing to instead feed on large groups of schooling fish. They are mostly seen off the west coasts of Vancouver Island but can be found from California to the Bering Sea. Offshores can travel in much larger groups as they feed on larger groups of fish, usually they move in groups of 20-75, but have been sighted in massive groups of up to 200.

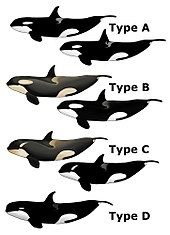

Researchers have also identified four distinct type of orcas in the southern hemisphere. These orcas reside in the Antarctic waters. Type A is a typical killer whale/orca, living in open water. They usually feed on minke whales and immigrate into and out of Antarctica seasonally.

Type B is smaller than A, it is more grey than black, and the white areas become stained yellow over time. It feeds on seals, and famously uses the method of “swamping” seals off floating ice shelfs. They drive up out of the water, slamming down to form large waves that push the seal off the ice.[4]

Type C is the smallest of the four types. It is mostly white and grey, experiencing the same staining that B does. It has only ever been observed to eat Antarctic cod.

Type D is relatively unknown but has a shorter dorsal fin than the other types. It is theorized to mostly eat water as it has been observed to prey on Patagonian toothfish. Both Type B and C live close to the ice pack, whereas Type A lives in the open water. Apart from their distinctly different colours, they each have a characteristically different eye patch. A has a medium white eye patch, B has a large white eye patch and C has a slanted forward eye patch. D has a small white eye patch.

Whatever the type, all orca are smart – they have the 2nd heaviest brain of all marine mammals (second only to sperm whales). They have complex vocal and behavioural cultures, leaving no doubt that in the water, this highly intelligent creature, by whatever name you wish to use, is a magnificent animal that deserves our respect.

- [1] Schuster, Ruth. 2018. Ancient Romans May Have Hunted Whales to Oblivion in the Mediterranean.

- [2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Killer_whale_attack

- [3] Bernstein, Paula. 2014. SeaWorld says “Blackfish” is “Propaganda”. The Filmmakers say they want a public debate.

- [4] https://video.nationalgeographic.com/video/00000144-0a27-d3cb-a96c-7b2f1df40000 video showing this happening